A+C's daily guide to new and exciting things, and how they hang together.

Aleatory and teleonomic, Birdsong bears a somewhat familiar resemblance to the Straub-Huillet school of adaptation and philosophy; however, Albert Serra plays a game of improvisation that branches this genealogy into a new space of chance. The document begat by duration here turns presence into an opportunity for digression, for leaps, for a poetic sense of contiguity and not continuity. The whole sums chunks arrayed, not morsels lined. One can sense the film was made on the fly, assembled into its form through smarts and luck. And it's silent, mostly. Save one piece of music, the soundtrack is an assemblage of sand and wind and broken branches, of waves, of inconsequent dialogue mumbled, of the world's little noises blown big.

by Ryland Walker Knight

by Ryland Walker Knight

Look, this isn't a cop-out—at least I don't think it is—but I tune out directors I hate until I forget their names. I remember all the directors I've ever liked working with as an actor—guys like Don Siegel and Robert Aldrich. The thing I feel directors have to realize today is that they must become like The Beatles: They must write their own material. It's really incredible that directors would allow someone else to write their scripts for them. I can understand that happening when a guy starts out, I suppose, but to make a career out of directing other people's work is all wrong.

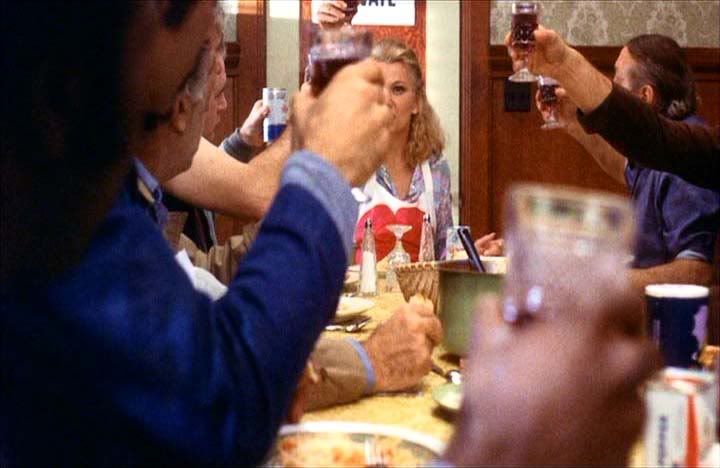

To counter our chill with a laugh (and a hug?), Film Forum has programmed the Breadlines and Champagne series, a month-long celebration of Great Depression cinema. The fun begins this weekend with an opening night screening of Wesley Ruggles' 1933 film, I'm No Angel, which stars Mae West and Cary Grant and costs a mere 35 cents (or a quarter for members). The weekend continues with two Franks: Borzage's Hooverville classic, Man's Castle, and Capra's punchy American Madness. I was lucky enough to catch a screening of the new print of the Borzage and wrote up some quick thoughts for The Auteurs' Notebook, which you will be able to read

To counter our chill with a laugh (and a hug?), Film Forum has programmed the Breadlines and Champagne series, a month-long celebration of Great Depression cinema. The fun begins this weekend with an opening night screening of Wesley Ruggles' 1933 film, I'm No Angel, which stars Mae West and Cary Grant and costs a mere 35 cents (or a quarter for members). The weekend continues with two Franks: Borzage's Hooverville classic, Man's Castle, and Capra's punchy American Madness. I was lucky enough to catch a screening of the new print of the Borzage and wrote up some quick thoughts for The Auteurs' Notebook, which you will be able to read  But don't stop there. Scroll down that page and you'll see all kinds of fun double bills, all at a 2-for-1 discount, including one helluva Valentine's Day, programmed by Bruce Goldstein to pair My Man Godfrey (service would save the day, wouldn't it) with Easy Living (perhaps most famous now for its early Sturges screenplay). If that kind of night out (complimented by a meal and drinks, if not flowers, I trust) does not warm the soul, I cannot imagine what will. Of course, two days earlier there's a new print of Young Mister Lincoln screening with The Tall Target, if your soul needs that kind of uplift. Night Nurse plays Feb 17, Hawks' Scarface on the 21st and King Kong helps close the month before five more double bills to start March. I'm going to try to enjoy as many as my meager wallet and my stuffed social calendar will allow. (And if that's not enough for you, there's something called The Human Condition coming back by popular demand April 8th. That one might tell you some things.) [x-posted at VINYL IS HEAVY]

But don't stop there. Scroll down that page and you'll see all kinds of fun double bills, all at a 2-for-1 discount, including one helluva Valentine's Day, programmed by Bruce Goldstein to pair My Man Godfrey (service would save the day, wouldn't it) with Easy Living (perhaps most famous now for its early Sturges screenplay). If that kind of night out (complimented by a meal and drinks, if not flowers, I trust) does not warm the soul, I cannot imagine what will. Of course, two days earlier there's a new print of Young Mister Lincoln screening with The Tall Target, if your soul needs that kind of uplift. Night Nurse plays Feb 17, Hawks' Scarface on the 21st and King Kong helps close the month before five more double bills to start March. I'm going to try to enjoy as many as my meager wallet and my stuffed social calendar will allow. (And if that's not enough for you, there's something called The Human Condition coming back by popular demand April 8th. That one might tell you some things.) [x-posted at VINYL IS HEAVY]

Yet it would be entirely too facile to suggest that When It Was Blue is Reeves’ freedom tract, an overcoming of an agoraphobic attitude toward the greater world. For one thing, although Reeves always tends to incorporate some autobiographical elements in her work, she does so in a highly complex, mediated way, and to simply read “Reeves” off the surface of the work is to do both films and maker a grave disservice. Nevertheless, the restlessness and anxiety that permeates When It Was Blue, in particular its engagement with the problem of self and other, the female eye and body making itself genuinely vulnerable in global space, is a feminist and a political issue, and one that expands the mythopoeic achievements of Brakhage in a distinctly grounded, even urgent new direction. (And Brakhage’s work, when reread through Reeves’ “use” of it, has a feminist undercurrent: a disarmed, quivering supplication before the visual universe that abdicates male prerogative, and that ought to give some of his feminist critics reason to reconsider their quick dismissals of his alleged modernist machismo.)

This kind of moral dilemma (“I can make this film against drugs if I help sell drugs”) is at the core of the most primitive Hollywood filmmaking. But something is wrong if a sophisticated director like Garrel indulges himself by messing with this cheap material. In a way, the depiction of intimacy with a twist of irony is a nouvelle vague device that goes back to À bout de souffle (1960). But after all these years, this particular mix of detachment and autobiographical narcissism that gave rise to dandyism has turned sour. In the beginning, there was a world outside and making films was a reaction to it. Now, there is no world left. It's just a matter of solipsism, a game of certain individuals playing with their minds and memories, and a group of admirers celebrating. That's why Sauvage innocence is an empty film.

by Ryland Walker Knight

by Ryland Walker Knight

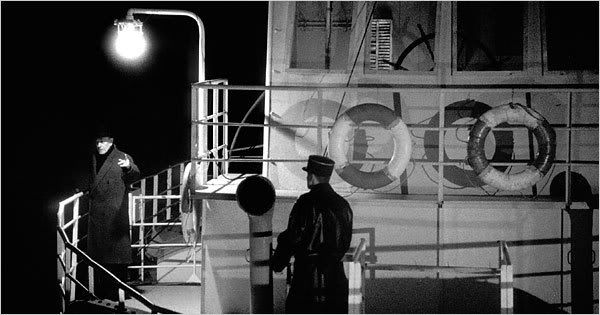

The film finally became available here last year on DVD from Facets Video, helping to demonstrate how much cinema as a “language” is more easily translatable than literature. For many years, Béla and I have had a running debate about the relation of the film (and, by implication, the novel) to my favorite novel in any language, William Faulkner’s Light in August (1932), which also focuses largely on the simultaneous events of a single day in a depressed, flat rural area as seen through the consciousness of several alienated characters—alienated from themselves as well as from one another—including a fallen patriarch who observes all the others called Reverend Hightower (a name and figure that already anticipates some of the structure and vision of The Man from London), and who might have served as his community’s conscience if they all hadn’t deteriorated into an apocalyptic, post-ethical stupor. Béla doesn’t see any connection because he doesn’t care for the Hungarian translations of Faulkner, and it’s true that one could also trace many of Faulkner’s methods to those of Joseph Conrad. But I also can readily acknowledge that the sarcastic wit of the story is quintessentially that of Eastern Europe.

by Ryland Walker Knight

by Ryland Walker Knight

curator at artandculture dot com.